Feature

Spurred by a desire for greater supply chain resilience, companies are increasingly reshoring and investing in new and updated manufacturing operations in North America.

For the past decade, global management consulting firm Kearney has produced an annual Reshoring Index report to uncover the mindset of top U.S. executives surrounding reshoring. This year—for the first time—the results prompted Kearney Partner and lead author of the report Patrick Van den Bossche to declare that the reshoring trend is real. is real.

“When we started the Reshoring Index, the intent was to gather objective data about a trend that was being reported in the press and by politicians, but that our clients weren’t talking about at all,” he said. “My colleagues and I have been skeptical, but this year we’re convinced.”

Specifically, among the CEOs Kearney surveyed, a full 96% report they are evaluating their reshoring options, have decided to reshore, or have already done so. That represented an increase from 78% in 2022’s report.

More evidence that reshoring’s time has come, added Van den Bossche, are the sizable investments being made in manufacturing infrastructure.

“Last year, new plant construction represented about $100 billion, while another $750 billion was spent on upgrades, automation and other updates to existing plants. That’s $850 billion,” he said. “Put that in the context of gross domestic output, which is about $6.3 trillion, and $850 billion is about 13% of that. It’s the equivalent of a company investing 13% of its annual revenue into manufacturing.”

Likewise, 71% of CEOs report being asked by their Board of Directors to consider reshoring manufacturing operations closer to the U.S., nearly double the number from the year before, noted Van den Bossche. “If the Board is talking about it, then so is Wall Street. And, indeed, the number of mentions about reshoring in annual reports has also risen.”

At its core, reshoring is the antithesis of off shoring, a trend that started roughly 60 years ago, noted Harry Moser, founder and president of the Reshoring Initiative.

“U.S. manufacturing costs are consistently higher than in most other countries. Compared to China, for example, we’re about 40% higher,” he said. “Companies sought to offset that by moving manufacturing overseas— often to China—where they could get good enough quality at a lower price.”

That ultimately led to an import/export trade deficit of $1.2 trillion in 2022 and has cost the U.S. roughly six million manufacturing jobs, Moser noted. His non-profit consulting firm works to support companies seeking to bring American manufacturing back to the U.S.

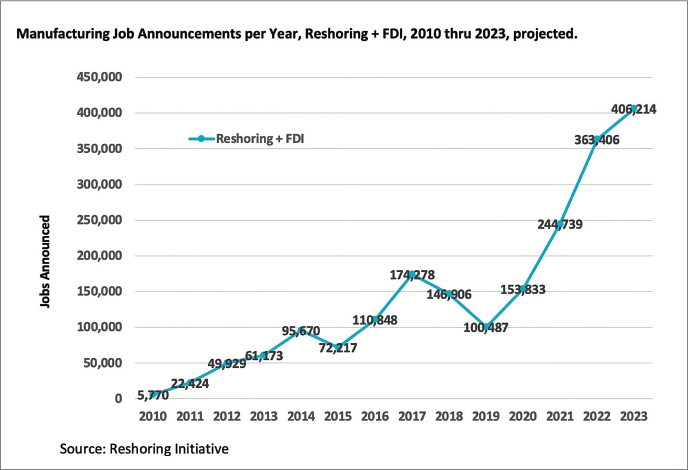

Moser has seen a long-term surge in reshoring. “In 2010, when we started, we identified approximately 6,000 jobs being reshored. In 2022 it was more than 360,000, or about 60 times higher than it was 13 years ago.”

Factoring in current reshoring and manufacturing investment announcements— including from businesses headquartered outside the U.S.—the Reshoring Initiative projects more than 400,000 manufacturing jobs will be announced as returning to the U.S.

Here is a breakdown of the reshoring trend, what it comprises, the challenges and opportunities companies face, and the technologies supporting a more geographically distributed supply chain.

The uptick in reshoring as a trend has been driven by the challenges supply chains have faced over the last several years, observed Kamala Raman, vice president and team manager at Gartner Supply Chain.

“It started with Brexit, then the U.S./ China tariffs, and then the worsening geopolitical situation, followed by COVID, which prompted widespread global supply chain disruption,” she said. “Companies realized that prioritizing low-cost global supply chains also exposed them to tremendous risk.”

Raman pointed to the automakers forced to park thousands of new cars in the middle of their production because of a shortage of computer chips. “If you need 100 parts to build a product and one is stuck somewhere, then you still cannot ship that product. While it is impossible to regionalize all manufacturing, companies now believe that investing in regionalized supply chains for specific products based on their margins will actually be cheaper in the longer run,” she added.

A related concern, added Van den Bossche, is a desire to reduce delivery lead times, both within the supply chain and to the final customer. “Especially with interest rates rising, capital is becoming expensive. Therefore, sitting on a lot of inventory—including products traveling across the ocean for six to eight weeks—is starting to become more expensive.”

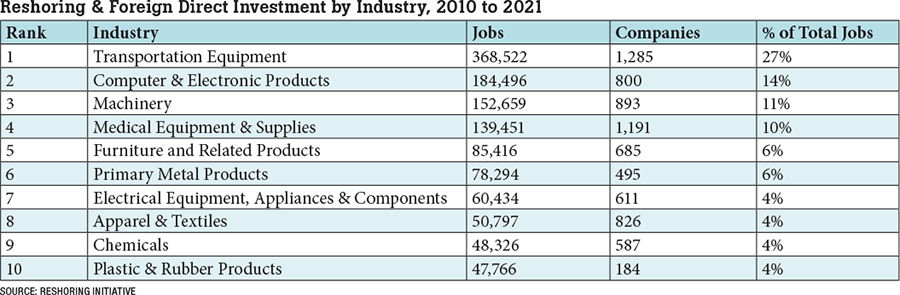

Up until 2021, the top three industries reshoring to the U.S. were transportation equipment, computers and electronics products, and machinery, said Moser. (See table above.) In the last two years, however, the U.S. government’s Inflation Reduction Act’s (IRA) Clean Energy Provisions and the CHIPS Act have accelerated growth in the electrical equipment and chemicals industries. That’s because electric vehicle (EV) batteries are classified as electrical equipment, and semiconductor chips and rare earth minerals are classified as chemicals, he noted.

“Companies are responding by locating EV battery factories next to traditional automotive assembly plants that are being converted from combustion engine to electric, both in the southeast and stretching up into Ohio, Michigan and Indiana,” he said. “EV batteries represent about a quarter of the weight of the car; it makes more sense to produce it a mile away rather than have to ship it a thousand miles or more.”

Likewise, Moser continued, government incentives have underpinned investments in semiconductor chip manufacturing facilities around the country, including Texas, New York and Arizona.

Reshoring and nearshoring

Moser, Raman and Van den Bossche agree that the term “reshoring” should be considered an umbrella term that encompasses several different strategies for diversifying a company’s geographic supply chain.

Moser outlined three separate strategies that fall under the scope of reshoring:

- Reshoring, when an American-headquartered company returns some or all of its manufacturing operations to U.S. soil.

- Foreign direct investment (FDI), with non-American companies building manufacturing operations in the U.S.

- American or non-American companies shifting their supply chain from offshore to the U.S.

Related strategies include friend-shoring which has two main locations: Nearshoring to Canada or Mexico, or to friendly countries outside North America. The biggest advantage Mexico and Canada offer is simply geographic proximity, coupled with strong manufacturing-based economies, skilled workers and free-trade agreements with the United States. Mexico specifically is seeing such a dramatic rise in nearshoring that some are calling it the new China. According to A.T. Kearney Inc., American imports of Mexican manufactured goods have risen more than 25% to $402 billion since 2019.

While all these approaches help companies looking to reduce their dependence on Chinese manufacturing, “don’t mistake moves away from China for abandoning China completely— because it’s still an important market for many organizations,” cautioned Raman. Instead, they’re trying to de-risk their supply chains to be more resilient.

“A lot of companies are looking at a ‘China plus one or plus two’ kind of strategy,” she said. “For example, putting up a factory in Mexico or adding capabilities in Europe. It’s more of a nearshoring, regionalization or localization approach.”

In a recent Gartner Supply Chain survey, 95% of respondents reported intent to diversify their manufacturing and sourcing away from China.

“When we broke that down, 55% said they are executing on those diversification plans through nearshoring, adding one or two other locations outside of China, or moving to lower cost countries—such as India, Thailand or Indonesia—so they can remain in Asia where more market growth is occurring,” detailed Raman.

Reshoring challenges include labor shortages and supplier limitations

The other 40% responding to the Gartner Supply Chain survey said they’ve made reshoring plans but are struggling to execute them. That’s because there are many challenges surrounding reshoring.

One of the largest challenges, said Raman, is limited labor availability. “It’s extraordinarily difficult to attract labor to work factory jobs, which are often not temperature controlled, are physically demanding and can be highly repetitive,” she said. “The tightness of that market has led to the cost of hiring becoming astronomical.”

Van den Bossche agreed. He noted that, in response, companies who have reshored manufacturing to the U.S. are starting to look at automating and at other potential labor pools, such as persons who were previously incarcerated, or with disabilities. “They’re also looking for people who are more comfortable with digital technologies,” he added. “They need digitally native blue-collar people to operate today’s more automated plants.”

Another challenge is finding suppliers who can provide parts and materials at a scale and quality level comparable to the ones they worked with in China. If they can’t, then they’re still forced to operate a long, global supply chain to source the components they need.

“Having an ecosystem of suppliers here is very helpful to successfully reshoring manufacturing,” Van den Bossche continued. “Interestingly, the Chinese have figured this out. They’ve set up multiple suppliers of components in Mexico. Specifically, Mexico foreign direct investment has risen by 48% between first quarter 2022 and first quarter 2023.”

When considering reshoring manufacturing, American companies would be wise to look at helping their suppliers locate operations alongside them, he added. “That reinforces a relatively short supply chain while eliminating concerns about transfer of knowledge or a reduction in quality. Because many of them can find suppliers, but they’re often struggling to find the same quality they’ve come to rely upon from China.”

In addition to labor shortages and sourcing challenges, Moser notes that U.S. manufacturing infrastructure is much older than that located elsewhere in more recently developed countries. “The U.S. manufacturing peak was shortly after World War II, but in most emerging countries—and even in Europe—a lot of development has happened in the last 10 or 20 years. In many ways, the U.S. is not as automated or modern,” he said.

To help companies quantify the costs and risks of offshore versus domestic sourcing, Moser noted that the Reshoring Initiative has a free, total cost of ownership (TCO) estimator. It includes most of the factors mentioned.

MHI Solutions Improving Supply Chain Performance

MHI Solutions Improving Supply Chain Performance